That’s all he ever dreamed, really. To climb up in the big ol’ truck and sit in that leather air-ride seat and put his hands on the big steering wheel and shift that thirteen speed like a man, just once.

And I said, “John, that’s a shitty dream.”

When I was young, I wanted to fly in space and see the stars, all of them, and maybe see if I could figure out what’s all this talk about God.

Shit, John, I drove a truck and damn near froze to death one hundred and twenty miles north of Thunder Bay Canada. Minus forty-one degrees. The coldest I’ve ever been.

The best gift I ever received was a thermos of coffee that tow truck driver brought me. And that Canadian boy had some big balls coming out for me, and when I thanked him, he just said “I wasn’t doing much else today…”

My fuel filters all froze up, water in the diesel. Damn near lost my right foot to frostbite that trip.

I broke a drive shaft in a wind-whipped and freezing rain snowstorm blocking the upper entrance to the George Washington Bridge. I had to call a welder friend of mine to drive eighty miles through that mess. When he finally got to me, he said he wouldn’t lay in the slop and snow, so I had to weld it. I think I had eight million people pissed off at me that night.

Then there was that girl Loralie, always broke and hustling drinks at the bar. A pretty, skinny girl. She was married, I was told, something she never confirmed or denied. I knew she lived with some guy. He sold heroin and coke and weed. I hated him, for reasons lost to me. I was no better a man than he was.

Sometimes when I was back off the road and didn’t want to go home, I’d park my tractor out back Turf’s bar and sometimes Loralie, she’d stay in the sleeper with me. When we got tired of pretending we were in love, we’d sit in the cab and look out the dirty windshield at the hookers and dopers doing hooker and doper stuff in the cars parked next to us. Laughing and making up stories about the characters and the weird little show playing out before us.

Sometimes I’d take her with me on short trips, like a load of tangerines into Boston or pulling onions into Toronto. She was the DJ, fiddling with the radio dials. She smiled and laughed when the hundred-thousand pounds of us hit a pothole and the whole rig shuddered and shook.

I didn’t know she had a kid. I suppose I should have figured she did, or asked. I was kind of single-minded in those days, John. I didn’t ask a lot of questions or pay close attention. I was just tired of being alone; I suppose. Loralie, she was good company. We laughed a lot, and she had a pretty warm smile, and I liked her dirty blond hair and her skinny face with her big green eyes.

One night up near Montreal, we got stuck in the worst white-out blizzard I ever lived through. Loralie, she was crying because she had to get home to her kid. Her mom was watching the boy while she ran with me. I swear to God I ran that three hundred miles in the low range and riding that clutch to get her home.

When I got back to the shop, me and this other kid, we pulled that tranny, there wasn’t shit left of that clutch. The guy I worked for was pissed at me, but I figured it was just his turn to be pissed at me. It seemed like every day was somebody’s turn to be pissed off at me, except Loralie. She was never pissed at me. Even if I gave her a reason to be.

Then one night, I got home to the bar, and she was nowhere to be found. I just figured she went back to her man or her kid, and I was sad, but I didn’t cry or any of that shit. I just got good and drunk, and the next day took another load, Detroit, as I recall. It’s kind of hard to remember. Those days and the towns all run into a blur. I think I liked the blur. I must have. I lived in it long enough.

One night, late ‘78, I think maybe August, I was out back of Turf’s smoking a joint and hanging with the hookers and dopers. I was ribbing and jiving, watching some of the bar girls in short sweaty dresses and tank-tops dancing with bottles of warm beer and cigarettes in their hands, out under the streetlights on that old railroad cinder parking lot.

This girl Patty, Loralie’s friend, runs up to me. I could tell she’d been crying, and she handed me one of those little square photo booth pictures of Loralie and she told me she was dead from the cancer.

I didn’t even know she was sick, but again, I didn’t always bother to ask. I told Patty I figured she’d just went back to her man. Patty said, “Loralie told me she never laughed so much in her life than with you, and she died in a lot of pain, and she said she was glad for the time you guys got to spend and she was glad you didn’t see her die. But she asked that I make sure to find you and give you this photo and ask you to not forget her.”

I took it and looked at her little face in the black and white square that seemed to smile through anything, poverty and drug dealer husbands and life at Turf’s and all the glory that encompassed…

And I was so goddamned sad.

I handed the joint I was smoking to someone and walked into the bar to get a drink.

Somebody was playing Don Williams Good Ol’ Boys Like Me on that Wurlitzer jukebox, gawky and loud. A few couples were trying to slow drunk dance to the song.

I ordered a shot of tequila and a bottle of Rolling Rock beer.

I drank both fast and motioned for another round, drank that, threw the empty bottle and shot glass at the mirror behind the cash register.

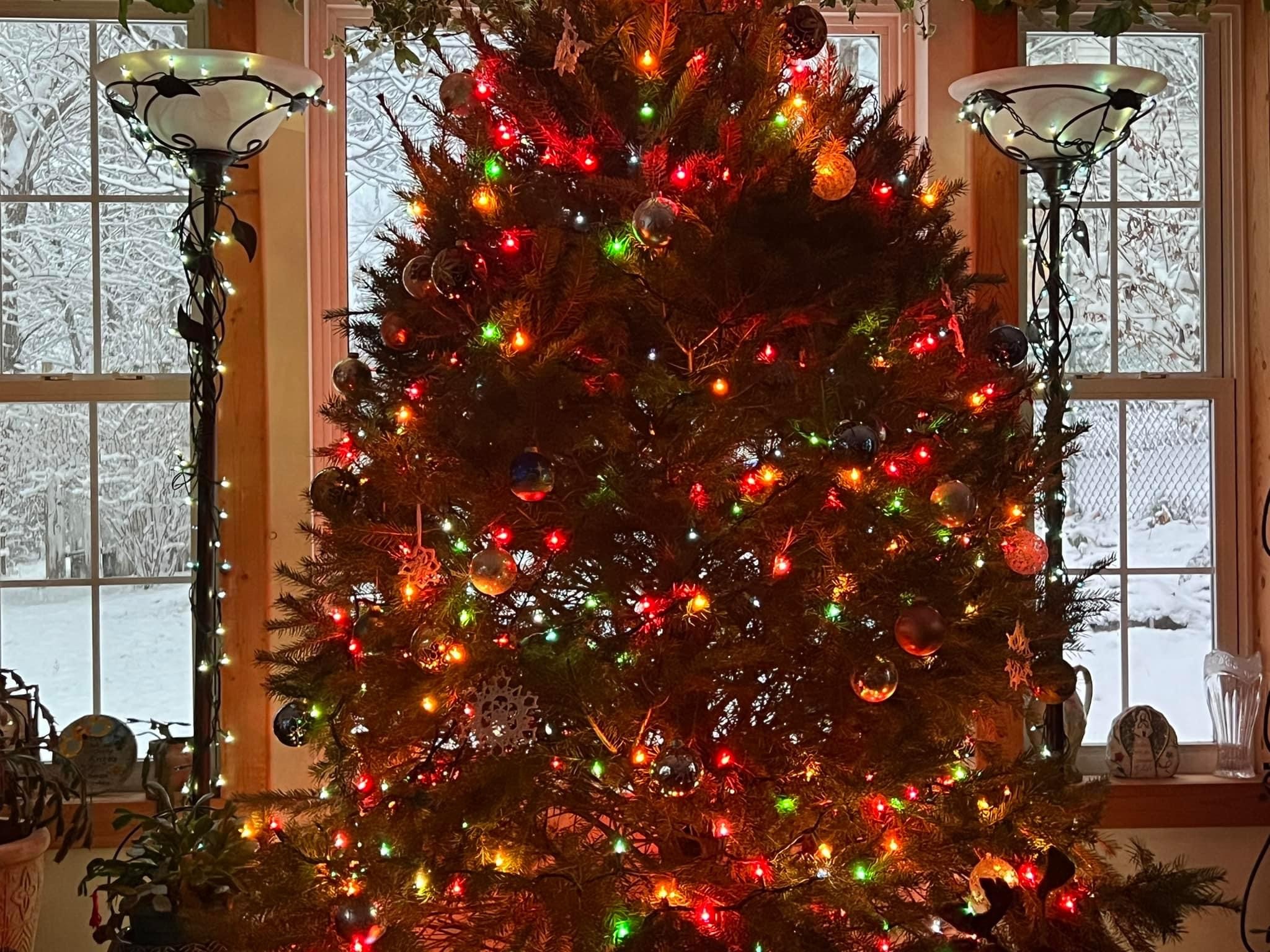

Jack, the bartender, ducked fast, and in the dim lights behind the rows of bottles of watered down and cheap booze the shards of glass and what beer remained sparkled for about a half second, and I remember thinking it was pretty. And it reminded me of the stars I wanted to see and that as a boy I wanted to fly in space but settled for that truck and this bar instead.

I reached out for the nameless slob nearest me, and I started to land head shots and a couple of good punches to his face. Then I realized it was some kid named Ronnie, too drunk to fight back. I was lucky. Ronnie would have beat my ass if he wasn’t half passed out drunk and high.

Jack grabbed me by my grimy t-shirt and threw my ass out onto the hard concrete and yelled I’d better let the night air cool me off.

I walked to the tractor, climbed in, sat there and cried and when I stopped crying, I headed out to find another load, but I’d never felt so far away from anything as I did sitting behind that big steering wheel.

That was my last time in Turfs, and I parked the tractor.

I heard the old Don Williams song for the first time in so many years, John. It took me on a journey that landed me right here, writing this to you.

So, that’s about all I know about trucking, but it ain’t like any of those cowboy songs that I ever heard.