A hot day alright, and them flies were in my face before the sun rose over that ocean of black and green. The morning’s ever present smell of eggs frying and bacon grease burning, and diesel exhaust and onions rotting in the crate.

The cook girl was pretty, not real pretty but pretty enough for me, and I wasn’t too pretty either, and the eggs were hot and the bacon wasn’t too burned. She snuck me breakfast first, before the rest of the field boys. I think she liked me. She gave me extra bread, and it was fresh baked with a lot of butter. She said, in jumbled words of Spanglish she wanted to fatten me up, but I was sure it was going to take more than butter to do it. She liked me, I’m sure, but more like a big sister, not looking to get laid.

I worried a lot because I always fucked it up with the farm girls. Their English wasn’t so good and I fell in love too fast. Them fields were so hot in the summer, there wasn’t a lot else to think about. I’d think about them field girls and falling in love. That was more fun than thinking about goddamn hot dirt and miles and miles of onions to be weeded.

By the time August rolled around, I was pretty sure there were bigger problems here on this earth than some fucking weeds, anyway.

The cook girl always made sure I got to eat first, and I didn’t want to wreck that. So I decided to not tell her straight up I loved her.

She smelled like sweat and her brown skin was powdered with the black dirt, but that wasn’t so bad. I smelled like sweat too, so we kind of smelled the same.

I think I was smart, but I wasn’t too sure. Everybody was always calling me smart, but I figured I couldn’t be too goddamn smart to be working in those endless fields. I looked up from the dirt one day when the temperature was topping ninety-five, only halfway through weeding a row. I stood there, and I swore to God if I didn’t get the fuck out of there, I was going to drown in that black and green sea. I never did drown, though. It’s probably real hard to drown in dirt. But more than one time, I wished I did.

Every summer was always about those goddamn onions, then into the fall, when we’d harvest. I hated onions. I hated weeding onions, and I hated grading onions. I hated dumping onions and stacking crates; I hated picking rots. I hated those fields, and everyone in them, except the girl who cooked for us. I swore one day I was going to learn how to speak Spanish good, like I speak English good, so I could tell her I loved her.

On a hot day I swear them fields felt like what Hell must have felt like, and since I was sure I was going there anyway for the thoughts I had about the cook girl, I’d be as ready as anyone for living in a pool of fire for eternity. At least that’s what the old lady told me every goddamn night.

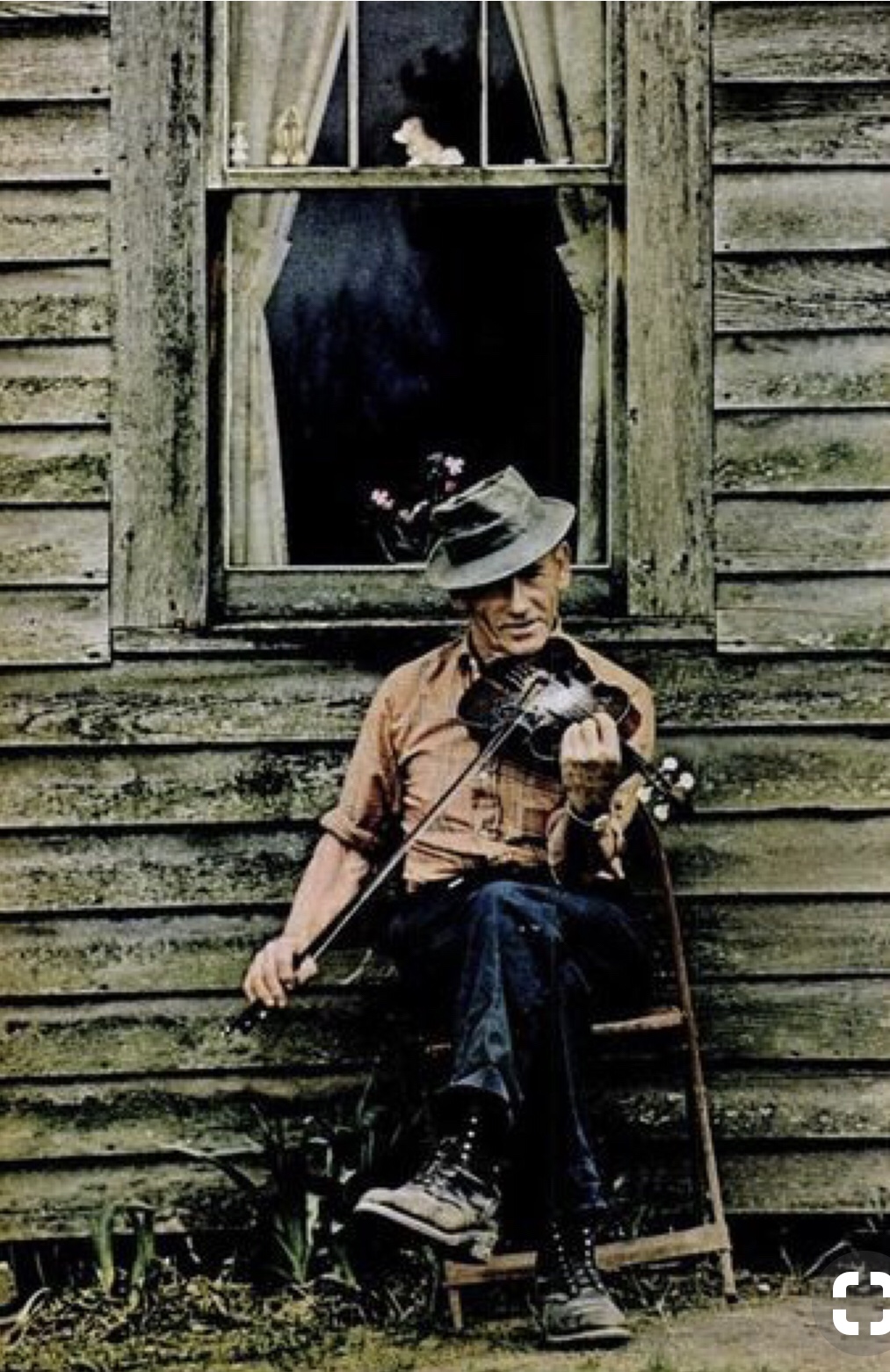

I’d come home with that black dirt caked thick on my skin. Patches of mud cracked open from dried-up rivers of sweat. The skin on my back was burned by the sun until it bubbled up in blisters and it felt like that sizzle-burned bacon I had for breakfast. And I wasn’t in no mood for hearing about no Jesus nor Hell. I just wanted to wash off the black muck and go to bed. But first I had to learn me some Jesus and sing that song about an old rugged cross and listen to some Tennessee Ernie Ford, not no fun music ever, no songs about being in love with the cook girl, but more a about crosses and promised lands burning’ in Hell and all that shit.

The old lady had pictures of Jesus or God or somebody up there on the plaster wall under a painting of President Roosevelt. Underneath the pictures was a clay statue of some praying hands. I know Jesus was important to the old lady, but I didn’t see where it fit in to my life, what since all I seemed to think about was them goddamn onions and the cook girl.

I told the old lady one time maybe we should have a little fun now and fuck the promised land and them stupid onions. She didn’t like that any one bit, and she slapped me. The next day there I was again, eating my bacon and trying to say I love you in Spanish, while looking at the mist rising off them goddamned fields. I was often amazed how something as pretty as an onion field could be in the first light if the morning, with the slow coming sunrise and the rising and swirling mist, could try again to kill me by four in the afternoon.

I figured, from the perspective of my handful of years, and five feet tall, that a row of onions was about a mile long, one way, maybe ten miles long. A weeder walked bent over the whole time, and don’t you dare miss a single goddamn weed. When you reached the row’s end, you’d turn around and weed the other side of the row. The whole process struck me as asinine. We’d pull out the tiny weeds by hand and throw them in a bag, then dump the bag back in a ditch bank at the row’s end, where they could grow again.

Big Joey, the farmer, was a big man with a big beer gut, and not too goddamn smart, but smart enough, I suppose. He smelled bad, like dirty pants and sweat. Not the same sweat smell as me and the cook girl. Big Joey smelled like it was a long time since he was clean. He took me with him in his truck one day and when I asked him where we was headed he said, “We are going to pick us up a load of wets,” and he said I was a good worker and I could be boss of them wets and get out of them sweaty hot fields, if I played my cards right.

I don’t play cards, and I didn’t say much, so I felt like a pussy, but as we rode in the truck, I was getting real mad. He called the cook girl a wet too and asked me if I liked her. Then he poked his fat dirty finger into my ribs, like we was pals. I didn’t like that he called her a wet, I didn’t like that one bit. I sat in that truck smelling Big Joey and felt my bare sunburned back running against the dry vinyl of the beat-up old trucks bench-seat. We picked up eight Mexican farm-hands, Joey’s ‘wets.’ Five of them was a family, mother, father and three kids, two about my age.

When we got back to the farm, Joey was being a real asshole to the new people, I found a two-by-four, about 5 feet long on the ground by one of the barns. I hauled way back, and slammed that board into Big Joeys kneecap as hard as I could. He buckled to the ground, and I walked away from them fucking onions for good.

He comes limping by the old lady’s house a few days later, standing on the tiny front porch, speaking to her though the wood framed screen door. He said he wasn’t going to call the cops because I was just a kid. I screamed out the cracked front window that he didn’t want the cops to come and see how he treated his hands, that’s why he wasn’t calling nobody. Then I yelled out louder, he better stop calling them wets before I bust his other knee.

That was the end of my time onion farming. I never did see the cook girl again, so that made me pretty sad. I don’t dare go nowhere near Big Joey’s farm. I think he’d probably kill me if I gave him half a chance.

The old lady said Jesus was mad at me for busting Big Joey’s knee. I figured if Jesus was siding with that asshole, I didn’t want anything to do with him neither. So that was pretty much the end of me and Jesus too.