It feels a lot, tonight, like November 1963, and I have liver and onions and mashed potatoes sitting on my plate. I wasn’t eating any of that, and my father wasn’t letting me up from the table until I did, and the liver was stone cold. I learned the meaning of the word ‘stand-off’ in that little kitchen, in the little stone house by the muddy, weed-filled pond. It wasn’t a lake, dad; it was a goddamn mud-hole. We should settle that once and for all.

I’d sit there all night; I wasn’t touching that dinner, and my father wasn’t budging; he had the radio and his newspaper. He was in it for the duration. He called me ‘bullheaded,’ and I reminded him I was his son. We’d sit there, on these occasions, until maybe 8 pm, and we’d declare a draw, and I’d go to bed, better hungry than poisoned by cold mashed potatoes and liver.

My dad didn’t like Kennedy, but he didn’t want him dead either. He understood there was a line that couldn’t be crossed, and there were rules that had to be adhered to, like eating the food put before you, no matter how disgusting.

That day the slug blew off the back of Kennedy’s brain, I saw fear in my father for the first time. I was six, and the world turned dark and suddenly cold and frighteningly small that November Friday. I’m quite sure it was the first moment I felt his fear.

Cronkite cried, and Huntley and Brinkley reported on the tiny black and white TV.

I was born just before Sputnik went into space, but the spectacle of spacemen and heroic deeds of Gagarin and Glenn were lost on this day; I asked my dad if the Russians were coming again to kill us. I was six, dad, fucking six-years-old, and I remembered the missiles in Cuba, in 1962, we saw them on that same little TV, and I was scared then too, but this was a different scared. Besides, we’d been saved from the Soviets by Lieutenant Kennedy, and now half his skull was blown off and laying on the trunk lid of some big Lincoln Continental in Dallas. The teachers cried, and the principal cried, and on the way home, I saw a cop crying, and I was scared.

It was Saturday the next day, and I remember the fear in my sister’s eyes when she realized American Bandstand wasn’t going to be the little black and white TV that day, just talk of Soviets and Cubans and dead presidents.

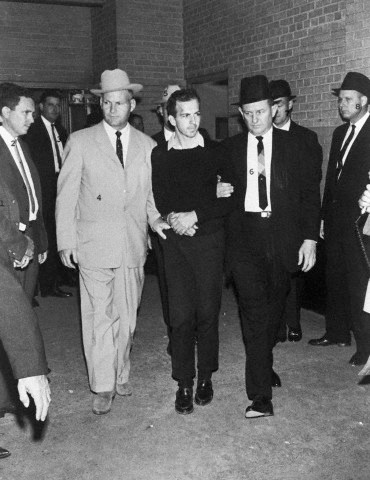

Then the next day, Sunday, we went to church, and later that day, some guy named Ruby shot and killed Lee Harvey Oswald, the guy who everyone said was a Russian and who killed Lieutenant Kennedy. I was more confused than ever because all the Russians I’d ever heard of were named Khrushchev and Gagarin and Boris and Vladimir, not Lee Harvey Oswald, and I was still pretty scared about missiles from Cuba. I was scared because my sister was scared that American Bandstand might never be on again.

A couple of days later, Grandma came to our house, and we ate some turkey, and I was pretty sure, within days, there’d be a big picture of JFK up on the wall, above her piano, next to FDR and Jesus.

Later I went outside with my dad, and we put up some of those huge fire-hazard Christmas light bulbs purchased at a Woolworth’s somewhere in the late 1950s. Even though each of the three strands of bulbs my dad proudly owned had a big “UL” label—Underwriters Laboratory—that was supposed to convince me those big, hot bulbs wouldn’t burn the house down. It didn’t.

Dougie Hulseapple came by later that day, and we formed a plan to avenge the death of Lieutenant Kennedy because we both were scared of Soviets and bombs and Cubans and men named Ruby. It was getting dark way too early because it was November, so if there was any avenging to be done, we’d better get it done before dark when our moms with call us home.

It was like that in 1963 and feels a lot like I’m having liver and onions and mashed potatoes for dinner tonight too, and dad, it’s scary like that, and it still feels like the Russians are coming, and I think it’s going to be a long night.